A hypothesized and randomly factual History of Tarot Cards

What follows is the story of a deck of cards and all the more-or-less

believable claims made about its origin. This brief history was compiled

following sources that attempted accurate historic recalling instead

of the most commonly shared semiotic, occultist story.

However,

despite all efforts, the found sources told a convoluted

tale due to the misinterpretation of age, sources and authorship common

to any ancient texts on magic and mysticism (Dummett, 1993). As such,

the following text will recall the disproven stories that were told

about the origin of Tarot, some factual sourced material and a modern

description of its usage.

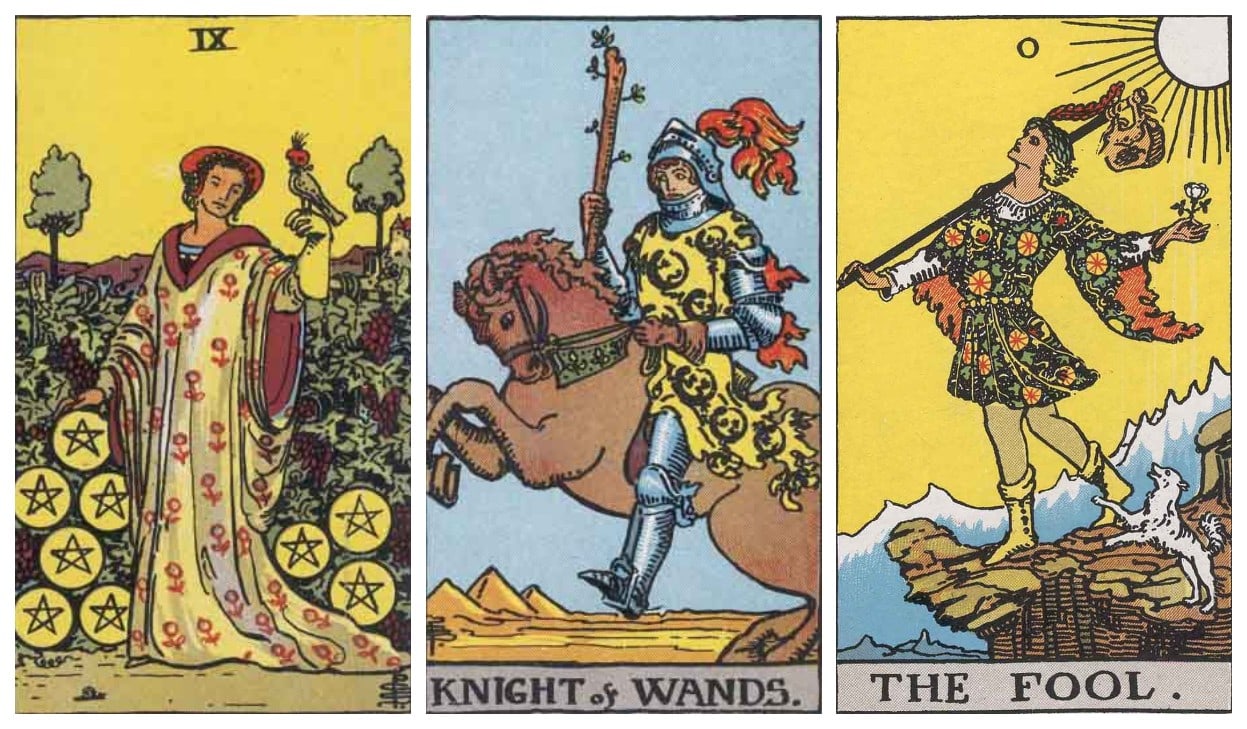

When we talk about Tarot cards, we are talking about a deck of playing cards composed of ten numeral cards and four court cards (Jack, Knight, Queen and King) for each of the four suits (Swords, Batons, Cups and Coins). Alongside these more common cards, Tarot includes 22 ‘trump’ cards with allegorical illustrations. The trumps form a sequence, usually numbered from 1 to 21, with the single card of The Fool being separated (Decker, Depaulis & Dummett, 1996).

This specific deck of cards’ history begins at the bottom of a well in 1440’s Northern Italy, where we place its first appearance in history. From there on we can easily find links to the common usage of these cards in Northern Italy; from Milano to Bologna and Ferrara (Steele, 1900). These cards, initially called Trionfi and then Tarocchi, are thought to have been intended for card games, regardless of their occasional usage in future-telling (Dummet, 1993). This finding helps us trace a factual beginning of Tarot but leaves an open question as to how these cards gained their place as the primary tool used in modern occultism and mysticism for cartomancy.

While this is where the story begins to get intricate, it is clear that the first wide spread future-telling performance appeared in France in the 18th century. At this point, the history of Tarot was to be influenced by what each fortune teller imagined the history of the cards to be. To fully reveal this, I will first attempt to map the most notable occultists that used the cards and wrote historical notations about their deviance, and the stories they told about them.

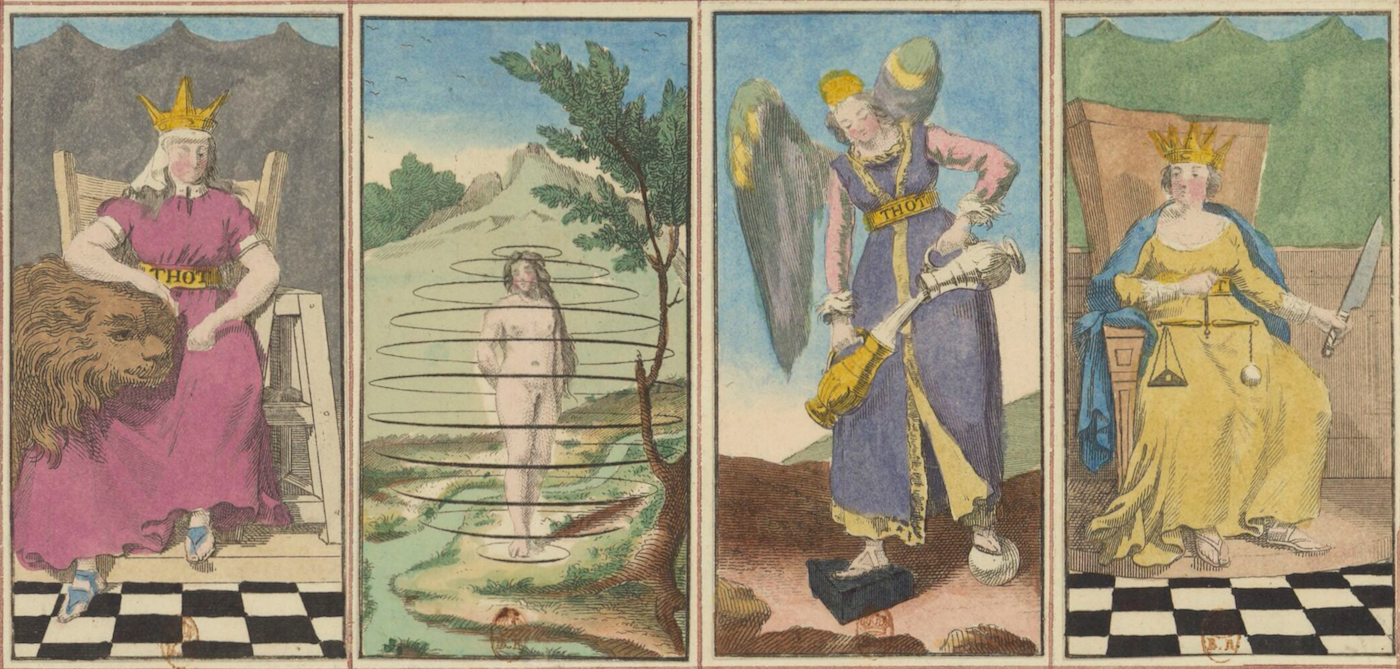

The first encounter we have between Tarot, magical theory and practice happens in the Monde primitif, an incredibly long essay about Tarot cards written in 1781 by Antoine Court de Gébelin. With this text, the pastor began what would be the endless repository of arcane esoteric wisdom within Tarot that would follow the cards for generations (Chisholm, 1911). In this text, Gébelin attributed the cards’ origin to ancient Egypt, a theory that is to this day accepted as truthful. This belief was based on an erroneous link to The Book of Thoth, an ancient Egyptian text about magic that is believed to have been spread through Europe by Romans. This belief was then substantiated with a similar essay by Comte de Mellet (Decker, 1993). Promptly, a Parisian fortune teller named Jean-Baptiste Alliette, professionally known as Etteilla, having found these theories, adapted the esoteric view of the cards to his own uses. He switched his own practice from traditional French piquet cartomancy to the use of a self-made Tarot card deck. This deck was based on the previously shared Hermetic ideologies and was named The Book of Thoth (Decker, 1993).

The next fundamental spin that was applied to the cards’ background was done by Éliphas Levi, another French esoterist. Levi repudiated Etteilla’s theory and integrated a version of the cards that were closer to the original than his own Cabalistic magical system. While Levi’s understanding of the cards’ travel from Egypt to Judea and into Jewish tradition was historically mistaken, it nonetheless revolutionized Tarot in ways that survive to this day. His Cabalistic theory about signs being letters, letters being absolute ideas and absolute ideas being numbers can still be seen in modern iterations of Tarot.

At this point, Tarot’s journey speeds up as the cards leave France and become absorbed into new esoteric movements like Swedenborgianism, Mesmerism and Spiritualism (Decker, Depaulis & Dummet, 1996).

Before we make another jump through time towards the next relevant development of Tarot, I will share the last of the three false widespread theories about the origin of Tarot (the first two being ancient Egypt and Judaism, despite the latter’s influence on modern Tarot).

This last theory is harder to trace back to one esoteric influence, and it claims a Chinese origin to the cards. This is most likely due to the similarity between Tarot and the I Ching, a divination manual from around 1000 BC. This manual was grounded in cleromancy, i.e. the production of random numbers with the purpose of predicting divine intention. However, there is no traceable connection between Chinese cleromancy and Tarot divination. Modern analyses of Chinese Tarot divination draw a direct correlation between Western occultism and Tarot divination, leaving little room to imagine any direct causation starting from China (Fu, Li, Lee, 2002).

The next big step will bring us to Britain in the late 19th century, to the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn. The Golden Dawn was a secret society devoted to occult Hermetic Kabbalah and one of the largest single influences on Western occultism as a whole (Jenkins, 2000). While the society itself had a wide curriculum including astrology, alchemy and geomancy (soil divination), our concern at this moment are their links to

Tarot cards. In 1909, two mystics and members of the Golden Dawn, A.E. Waite and Pamela Colman Smith, published a deck of re-made Tarot cards through the Rider Company which reflected Golden Dawn’s magic system. Later, these cards became known as the Rider-Waite Tarot (Dean, 2015). This deck was based on the Sola Busca Tarot, with symbolism derived from Egyptian and Christian traditions and Levi’s descriptions. This deck has since become the paradigm and touchstone through which modern occultists think of Tarot. Between the distribution of this deck and the use of the cards in the Golden Dawn, it became axiomatic among followers of various traditions of mysticism that Tarot is an essential component of any occult science.

Today, Tarot is emblematic and incredibly wide spread as the most common future-telling method and device. Tens and thousands of different formats exist, often falling under the category of Oracle cards. While these do not share the clear formatting rules of Tarot, they are still used for divination and self-reflection purposes through the interpretation of allegorical illustrations.