Introduction

This Special Issue has been an attempt to understand games and rituals. Instead of an introduction, we will try to unravel this mysterious journey as well as keep questioning and collaging.

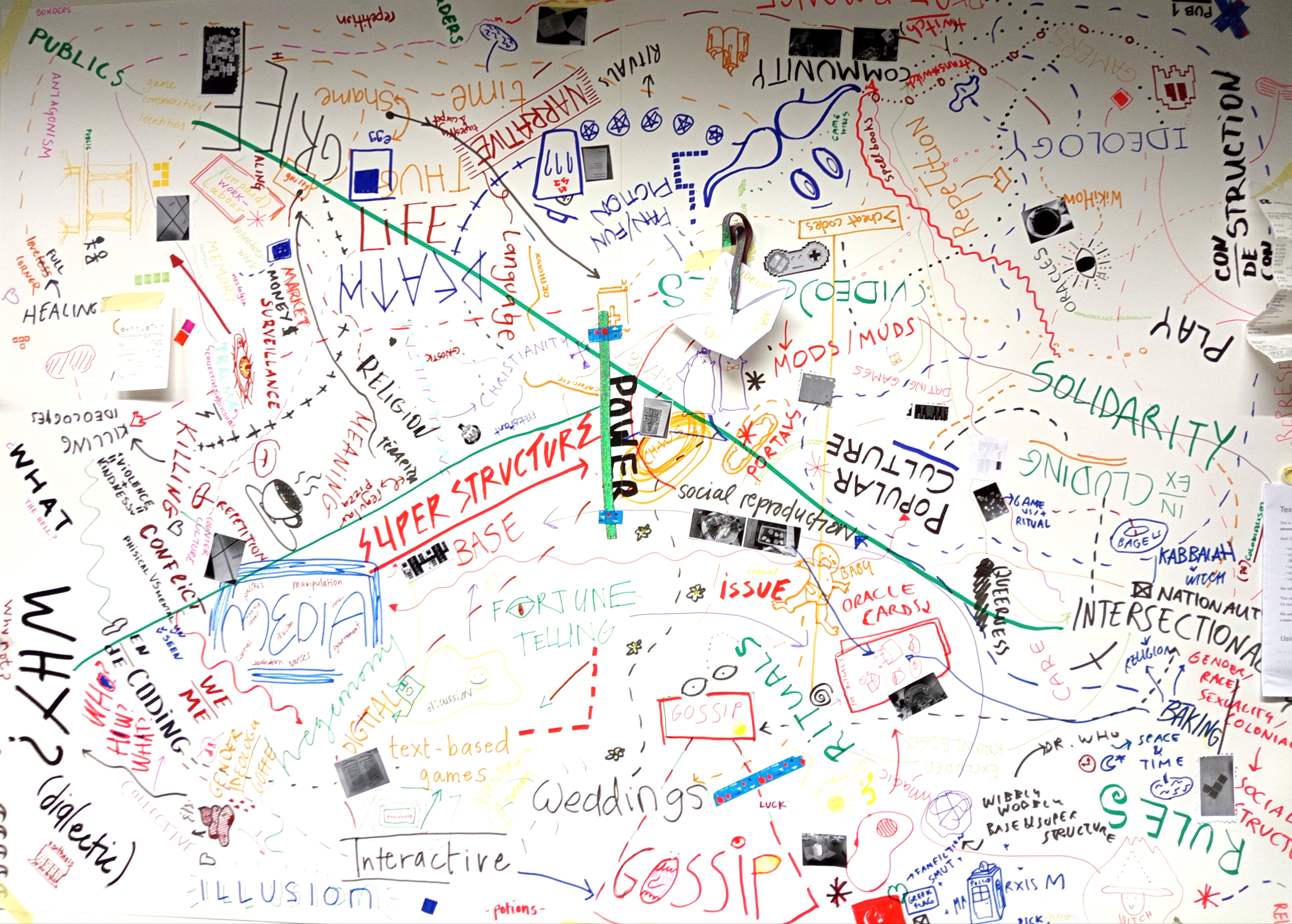

We mapped the common characteristics and the differences between games and rituals in relation to ideology and counter-hegemony. We practiced, performed and annotated rituals, connected (or not) with our cultural backgrounds while we questioned the magic circle. We dived into the worlds of text adventure games and clicking games while drinking coffee. We talked about class, base, superstructure, (counter)hegemony, ideology and materialism. We discussed how games and rituals can function as reproductive technologies of the culture industries. We annotated games, focusing on the role of ideology and social reproduction. We reinterpreted bits of the world and created stories from it (modding, fiction, narrative) focusing on community, interaction, relationships, grief and healing.

The eventual outcome of this process is a console, a magical object, a wooden container, a promise of healing. How can the unpacking of games, rituals, ideology and superstructure in relation to witch hunting become the midwife of a healing box? How can practices of healing and care work as counter-hegemonic acts which cure and liberate our souls and bodies from patriarchal and capitalistic fetters?

We didn’t manage to provide you with comprehensive answers or conclusive statements. The truth is that this wasn’t our plan. Our intention was to create openings for debate or even conflict, to map a territory, to invite those who would like to join us.

“What if you are playing tetris and the tetris gods give you something apart from the usual seven tetrominoes, like an unexpected pregnancy or the end of capitalism?” (Stephen).

Starting with rituals, we claim that they can be understood as instruments in the struggle for the exercise of power. Organized by repetition, they (re)connect the individual to the collective, creating a vision towards a given perception of society. Participation in this creative act is determined by several factors: a ritual’s function, its relationship to hegemonic power, a collective’s politics and objectives, etc.

“Ritual is a means of performing the way things ought to be in conscious tension to the way things are in such a way that this ritualized perfection is recollected in the ordinary, uncontrolled, course of things. Ritual relies for its power on the fact that it is concerned with quite ordinary activities, that what it describes and displays is, in principle, possible for every occurrence of these acts. But it relies, as well, for its power on the fact that, in actuality, such possibilities cannot be realized” (Smith, 1980).

“Ideology talks of actions: I shall talk of actions inserted into practices. And I shall point out that these practices are governed by rituals in which these practices are inscribed, within the material existence of an ideological apparatus(…)Ideas have disappeared as such to the precise extend that it has emerged that their existence is inscribed in the actions of practices governed by rituals defined in the last instance by an ideological apparatus” (Althusser, 1970).

Similarly, videogames create worlds. Often, those worlds mirror our own, reproducing certain ideals and values as norms through their narrative, game play, design. This trimester we explored world-building characteristics found both in rituals and videogames. We critically considered those worlds, identifying the key points and elements through which specific videogames and rituals circulate political, cultural and social values. While this world-building might be interpreted from an angle of implicit and explicit bias rooted in hegemonic values, we investigated the generative, creative possibilities of such characteristics.

“The main task of mass culture is to create, reproduce, and manage particular kinds of subjects — workers, consumers, individuals, citizens — required for current conditions. To perpetuate their own existence, mass media must succeed at representing the violent coercion of capitalist systems as natural laws: Of course you have to pay rent to live inside; of course you have to buy food to eat; of course you have to work if you want to survive. The production of a fungible, disposable and migratory working class requires the alienation and atomization of communities into individuals, which involves destroying the village, kinship structures, indigeneity, and many other previous forms of meaning-producing structures, leaving a gap which ideology must fill. While the fundamental structures of domination — racism, patriarchy, heterosexuality, etc. — form the bedrock of this ideological apparatus, the complexity of the always expanding and changing capitalist system requires an equally flexible set of subsidiary tools capable of rapidly adjusting ideology en masse. In general, media emerge not to meet the demands or desires of individual users but to accommodate what the predominant mode of production requires” (Osterweil, 2018).

Our intention was to look into rituals and their overlap with video games as a way to explore “forbidden” or otherwise lost knowledge erased by oppressive systems (e.g. witch hunts). Understanding games and rituals as gateways to alternative ways of relating to Nature, each other and (re)production of life, labour, etc, we played together by writing fan fiction and spells, developing rituals, analysing and creating games together.

“Sims as social reproduction: some values are certainly given by the game (make money to buy nicer things, progress in your career by doing tasks that improve your skill, charisma is a skill but not kindness) , but also ideology is put into the game by the player. The player chooses what to reproduce and often share in the “gallery” or on social media. Community being so important in this game then means that the crux of the social reproduction is happening when the choices you have made in the game are broadcasted. Did you create a heteronormative white thin nuclear family that made a lot of money? Or did you choose to play differently?” (Ada).

“The Communist Party of Second Life (CPSL) aims to be a Marxist, internationalist and revolutionary organization for all communists in Second Life. The CPSL aims to spread understanding of Marxism among SL citizens, to organise support in SL for the class struggle in RL, including all struggles of the working class against imperialism and the bourgeoisie, its state and wars” (keksakallu.klata).

“The act of the modder’s appropriation of the pre-existing game is also similar to Michel de Certeau’s cultural ‘poaching’. De Certeau’s everyday bricolors make do with remixing the privatized spaces and products of consumer society that they find themselves inhabiting and using. Rather than being passive consumers, ordinary people invent varied subversive tactics for stealing back the given of everyday life. De Certeau writes, ‘Everyday life invents itself by poaching in countless ways on the property of others’” (Schleiner, 2017).

Meanwhile, we explored the figure of the witch as a magical practitioner, as a resisting body, a border figure. “Federici presents the witch”as the embodiment of a world of female subjects that capitalism had to destroy: the heretic, the healer, the disobedient wife, the woman who dared to live alone, the obeha woman who poisoned the master’s food and inspired the slaves to revolt.” Behind the witch hunt, she uncovers a joint effort by the Church and the state to establish mechanisms of gendered control of bodies that immanently resisted newly instituted regimes of productive and reproductive work” (Timofeeva, 2019).

“Sorcerers have always held the anomalous position, at the edge of the fields or woods. They haunt the fringes. They are at the borderline of the village, or between villages. But sorcerers not only exist at the border: as anomalous beings, they are the border itself. In other words, the borderline passes through their bodies” (Deleuze, Guattari, 1980).

How does the understanding of the hunting of the witches that happened a few centuries ago in relation to the figure of the witch as a marginal, rebellious entity shed light on contemporary witch-hunting? How does this knowledge provide us with tools of empowerment, emancipation and resistance, and make us reimagine counter-hegemonic practices of collective care and healing?